NEW

Mikel Ojinaga: ‘Protecting our local varieties means maintaining the quality that defines us and the agricultural fabric that secures our future’

26 November 2025

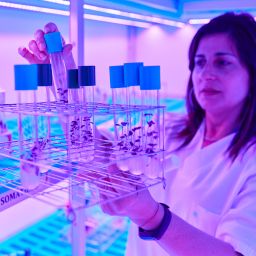

Viral diseases affecting peppers have become one of the main challenges for Basque horticulture, affecting such emblematic crops as the Gernika pepper and the Ibarra chilli pepper. Mikel Ojinaga has dedicated his doctoral thesis, developed at NEIKER and recognised with the Extraordinary Doctorate Award by the University of the Basque Country (EHU). This thesis studied several viruses and developed resistant local varieties that are now available to farmers.

Receiving the Special Award for this thesis is a great honour. What does this award mean to you and how valuable is it for agricultural research in the Basque Country?

I am very proud because this recognition highlights work that has been carried out over many years and has been truly collective, with the participation of many people from NEIKER and other entities linked to horticulture and plant health, both in the Basque Country and at the national level. For me, it is also a fitting way to conclude a project closely linked to my doctoral thesis, in which we have characterised in detail the health status of Gernika peppers and Ibarra chillies, with a special focus on viruses.

In addition, we have managed to make varieties resistant to Tobamoviruses, a group of pathogens that cause major losses in pepper crops, available to Basque farmers. The development of these varieties, the result of classical genetic improvement programmes, reduces the risk of epidemics and protects local production.

Your thesis focuses on two crops that are very much our own, the Gernika pepper and the Ibarra chilli pepper. What is so special about protecting the plant heritage of the Basque Country?

Protecting the Basque Country’s plant heritage is not just about saving seeds. It is also about preserving knowledge, flavour, culture and the local economy. Varieties such as Gernika and Ibarra sustain our gastronomic identity, are adapted to our agroclimatic conditions and provide essential genes for future plant improvement, reducing genetic erosion.

In addition, they help maintain competitive prices for the agricultural sector and strengthen the foundations of food sovereignty. If we only grew commercial peppers from other areas, we would lose diversity, differentiation and opportunities. Protecting and improving our local varieties maintains the quality that defines us, the diversity that protects us and the agricultural fabric that secures our future.

Viruses are one of the major challenges facing these crops. Why are they a problem for farmers, and which ones are the most harmful in the Basque Country?

These local varieties lack virus resistance genes, making them highly susceptible and causing a wide range of symptoms in plants and fruit, with a direct impact on yield and commercial quality. In the Basque Country, the predominant viruses fall into three broad categories: those transmitted by aphids, such as PVY and CMV; those transmitted by thrips, such as TSWV; and those transmitted by seed and mechanical contact, such as Tobamoviruses. In the thesis, we also describe a new Tobamovirus identified for the first time in Europe.

You discovered that some wild plants can act as a source of infection for crops. How can farmers protect their fields from this natural hazard?

Since 2017, we have observed epidemics of cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) in open-air chilli pepper plots in Ibarra. This virus, transmitted by aphids, completely devalues the quality of the fruit by making it fat, wrinkled and unmarketable.

After studying the epidemiology of the disease, we found that one of the main sources of inoculum is the wild flora surrounding the plots. We analysed numerous species throughout the year and confirmed the presence of plants infected with CMV, even in spring, before the crop was transplanted.

This shows that the surrounding flora acts as a primary source of infection. There are two options for protecting crops: introducing virus-resistant genes, as was done with Tobamoviruses, or using physical barriers, such as anti-aphid nets, to prevent infectious insects from entering from outside.

To this end, early detection is essential. How has the molecular hybridisation technique contributed to improving diagnosis at NEIKER?

At NEIKER, we have implemented detection using molecular hybridisation, a technique that allows large volumes of samples to be processed quickly and at low cost. It is more specific than ELISA, as the probes are designed based on the virus genome sequences, and it maintains a similar sensitivity.

Its great advantage is its multiplex nature, which allows several pathogens to be detected simultaneously in a single test. In my thesis, we used polysondes capable of detecting up to 21 viruses in a single assay, a tool that is particularly useful for screening large amounts of plant material and for large-scale surveys.

The best solution is to create resistant varieties. How can we make Gernika peppers or Ibarra chillies immune to viruses without losing their flavour and unique characteristics?

The most effective way to control viral diseases in plants is to have varieties with resistance genes. In our case, we have obtained lines of Gernika pepper and Ibarra chilli pepper resistant to Tobamovirus through classical genetic improvement programmes, introducing the L3 and L4 genes into both materials.

We applied a molecular marker-assisted backcrossing scheme to select resistant plants in each generation. In total, seven generations were necessary: a first cross with a resistant variety, four backcrosses to recover the organoleptic and agronomic characteristics of the original varieties, and two self-fertilisations to fix the resistance genes.

At the end of the process, resistance was tested by mechanical inoculation with Tobamovirus, and production trials were conducted to select the most productive lines that most closely resembled the original traditional variety.

These new resistant varieties are now available. What is the next step for them to reach the vegetable gardens of the Basque Country?

The most promising genotypes were registered in both the State Register of Commercial Varieties and the European Register of Protected Varieties.

As a result, there is now one variety of Ibarra chilli pepper (Irribarra) and two varieties of Gernika pepper (Gudari and Indartsu) that are resistant to Tobamovirus. These materials are accessible to all farmers in the Basque Country, allowing them to maintain the identity of their products while reducing the impact of these viruses.